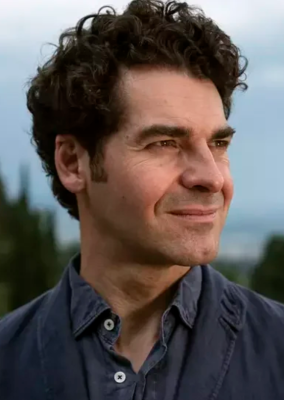

In this episode of the Liberal Europe Podcast, Leszek Jażdżewski (Fundacja Liberté!) welcomes Alberto Alemanno, Jean Monnet Professor in European Union Law & Policy at HEC Paris and one of the leading voices on the democratization of the European Union. They talk about business in light of the war in Ukraine, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Conference on the Future of Europe, and lobbying.

Leszek Jażdżewski: Could you tell us what was happening in Davos this year? It is a closed-door event, so what could you tell us about it? Is lobbying for change possible at the events like the World Economic Forum?

Alberto Alemano: Davos triggers a lot of negative feelings. It remains a very exclusive event, by invitation only, with a strong presence of corporate interests. However, the forum has changed over time. I had a chance to attend it a few times over the last 6-7 years, and I can say that even Davos has been partly democratized. The voices that are represented there change over time.

To give you some numbers: approximately 2,000 people were invited to the Congress Center, where most of the workshops take place. This year, around 500 of them were not corporate representatives, but activists, social entrepreneurs, academics, NGO representatives, who were there to contribute and diversify the voices.

Nevertheless, of course, the format remained very much top-down – the agenda is basically designed by the World Economic Forum on its own. Professor Schwab, the founder of the forum, has been running it for more than 50 years. However, the principle of the multi-stakeholder that has been successfully driving the Davos formula over these years, has changed over time. Now, not necessarily all voices were welcome, because the West decided not to admit any Russian citizens or government representatives by drawing a red line for the first time in history. This decision has raised some eyebrows but, at the same time, was praise by many corporate powerhouses and other participants – including myself.

So, something is clearly changing. One of the possible ways of changing Davos is to mainstream its ideas. How to do it? 95% of the program is streamed live, so everyone can follow its content. In this way, democratization has occurred – also in terms of the content. Then, there are, of course, numerous bilateral meetings between heads of states, governments, corporations, and civil society organizations – these are not necessarily publicly available, but this is part of life.

Davos remains a very interesting gathering, where multilateralism is no longer à la mode – there is some cooperation happening across and within sectors, across various regions of the world. Therefore, I would not throw Davos away as sometimes it is important to think about reforming what we have in place.

LJ: For some time, Davos seemed to be a trendsetter in terms of global topics. Apart from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which likely dominated the debates in Davos, did you see some trends in the area of citizenship or democratization? Is Davos a place where new ideas can be created? Are the global elites moving towards a specific direction? Or is it just business as usual?

AA: You are right that the World Economic Forum, and especially its Davos meeting, has been extremely successful in identifying new trends and putting them on the agenda. I remember my first time there, when it was all about cryptocurrencies. This year it was all about the metaverse. I do not espouse either of them, but these are the areas where a lot of investment is occurring at the moment and where the regulators struggle to understand what their role should be.

Davos is not about problem solving, it has always been about agenda setting. In this sense, we need to measure its success against the latter to understand to what extent Davos is still relevant and whether it is still capable to detecting topics and discussing them as a facilitator – the topics that are not discussed in the UN system, various regional organizations, or in coalitions of companies. When we evaluate Davos from this perspective, the formula still works, but it has to be modernized and become more participatory. The agenda itself should be more open to external suggestions.

I have been advising Professor Schwab to set up a citizens’ assembly, and to define the team that will be discussing these matters at the next Davos in January 2023. I have also suggested to set up an oversight body – similarly to what Facebook did. A kind of a supreme court of Facebook, making decisions. Davos should do the same – under international law, there should be a group of independent individuals deciding who should be in attendance and who should not.

This year, obviously, Russians were excluded from the forum, but why not the Chinese, given their discriminatory actions taken toward the Uyghur? Hence, the question is who is next? These lines seem to be blurry. It has to do with the complacency that I have witnessed once again – in particular, among the political and economic elites. Even this year, when they were basically put into a corner by journalists and people like me, who were brave enough to ask uncomfortable questions – even in Davos. The elites pushed back by saying that we need to remain optimistic, Europe speaks in one voice, and we are becoming more united – with NATO further expanding.

This is a very complacent attitude because they do not want to accept the reality. And the reality is that we are in the midst of a war that is not ending. We are not acting on climate – there is a lack of political will to adopt the technological solutions that already exist. There is no seizing the social awareness and the demand for action that already are in place. Hence, I do not see these phenomena in a very positive light – contrary to how it is being depicted by the elites.

At the same time, it is difficult to balance this sense of urgency that, for instance, Commissioner Timmermans has expressed at a private dinner with many state governments, and the delight to be able to meet in person after two years of the pandemic. I understand how difficult it was for the organizers to find the right balance between the two.

Finally, when it comes to strengthening and defending democracy in light of the erosion of democratic values across the globe, it was a big elephant in the room at this year’s Davos. There was only one session devoted to a democratic renewal, and it was rather trivial and shied away from. Another session, on trust, which I attended myself, revolved primarily around the Edelman report presented by Richard Edelman himself.

He shared some new insights and pointed out that once more citizens are losing trust in all the institutions – with one exception, the business sector. In the aftermath of COVID-19, companies have bounced back and now, they show more trust in institutions. However, how realistic is it to expect companies to fill up the void created by governments and to tackle all the issues from the climate change to social justice? I do not think this is very realistic.

It, therefore, became clear that the elephant in the room was there. There was not that much desire to talk about democracy. And there is a clear realization that – even for the interests of business and our capitalistic societies – unless there are stable and predictable institutions, business cannot thrive. This is probably the major takeaway of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

LJ: Could you tell us something about the work you did with your colleagues, trying to collect the data on how businesses reacted to the Russian invasion of Ukraine? Given that 100 days have passed since the start of the war, how do you see the situation of businesses in the region?

AA: The role businesses play in our societies, particularly in democracies and governments, is a very delicate one. It is very often overlooked by the political science and literature on the matter, because, historically, have tried to remain neutral vis-à-vis the political sphere in order to protect their own bottom line. They have often declared themselves as ‘apolitical.’ It is a great strategy not to lose market shares, because you might if you take a stance.

Obviously, this approach could not last much longer given the polarized society we now are a part of and the inability of governments to tackle major societal changes. In fact, companies themselves are subjected to greater scrutiny – both by investors and the public. Therefore, over the last decade, we have witnessed the emergence of greater public scrutiny of businesses, which is pushing the latter to take a stance on a variety of issues. The issues that companies would probably prefer to remain silent on, but now they can no longer afford to do that. Nowadays, not taking a stance means that you side with those who are questioning democratic values or even espousing discriminatory stances in our society.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has provided an incredible case study. It shows the stances that businesses are expected to adopt if they want to maintain their license to operate within the society. On February 21, in the aftermath of the invasion, together with a colleague of mine, Mark Hanis, who is also a member of the Young Global Leaders of the World Economic Forum and who runs a company of ethical consumption, we decided to team up and to set up what we called a ‘Ukrainian Corporate Index’. We have been tracking in real time the responses (or lack thereof) of various companies after Russia attacked Ukraine.

The companies range from McDonald’s to Meta and Facebook or airlines, taking a stance on the Russian invasion and monitoring if they were saying anything or whether they remained silent. These were assigned a red color (when there was no comment whatsoever) or yellow (when a company condemned the invasion). The companies that managed to do both – not only to verbally condemn the Russia aggression, but also to take a market decision to suspend the operations, investments, or closing the shops in the Russian market – were labelled as ‘green’ companies.

Through this color-coded system we managed to ‘name and shame’ certain companies and, at the same time, ‘name and fame’ those companies that appeared more responsible. The overall reaction to this project has been quite overwhelming for us, because it is something that we did ‘in house’ with a small group of analysts supporting us. In a matter of few days after the invasion, there was a public expectation that these companies would make it clear what they think about the conflict and take action.

It has been an incredible experience, which showed us that it is not only companies that have to act, but also that the employees that work for these companies operating in Russia and the customers have an incredible power. Power that goes beyond consumption, because it was all about using social media – naming and shaming CEOs or becoming whistleblowers and pointing to us the companies we did not have the time to yet include in the index. Sometimes, users were also indicating a mismatch between what the companies were saying (‘we are closing the shops’) and actually doing (maintaining the operations – e.g., in Moscow).

This stage lasted for approximately 5-6 weeks, and then we gave up, as the media have helped amplify the message. Now, we observe a plateau effect – the companies that were ready to leave Russia, have already left, whereas others decided to stay. Indeed, at the moment, there is less public pressure on them, because some of these companies argue that they need to maintain the production of hygiene or essential products and their availability on the Russian market. However, this issue raises a greater and broader ethical question: what is good for Russians? Do we want to boycott the current government in a hope that there will be a regime change and, at some point, help the Russian population?

2 million Russians left Russia and left for the Caucasian countries (currently, from Uzbekistan to Armenia) and nobody is talking about it. Something is happening out there, and the media do not report on that.

LJ: Since you are based in Paris, do you have any theory why so many French companies did not respond to the situation? Is it really the case? Do the French not care about that? Or maybe there is another reason for this lack of action?

AA: It is important to acknowledge that for certain industries it was easier to make a quick response. If you are a technological company, with very few employees and no production, basically no supply chains (like Google), it is much easier to decide to withdraw from the Russian market. On the other hand, if you are in the automotive or consumer products industry, this takes more time. There are companies that employ many thousands of people – how to do it in such a case? This was the major dividing line between various companies. Therefore, some companies had a chance to leave early, whereas others struggled more.

Secondly, certainly, some brands and companies felt less pressure because their population were not necessarily as sensitive to this issue as the societies in other countries. Here, German companies were under slightly more pressure than the Italian or the French ones, simply because, historically, the Italian and the French public is more pro-Russian. We saw several Italian companies (primarily related to luxury and food products) that stayed in Russia. We saw luxury products’ companies – in particular, a large group such as the AVHM – strongly resisting the pressure for a long time, until they eventually had to give up.

By the way, in the meantime, they significantly monetized their presence in Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, because there were many oligarchs and very wealthy individuals realizing that the ruble was decreasing in value, so they wanted to buy products when they still could do so. Numerous Instagrammers were keeping us updated on what was happening in Russia, which was very useful. However, once Meta decided to suspend their services in Russia, we were no longer in touch with them.

Now, Russia is becoming increasingly isolated from various perspectives. This, however, further strengthens Putin, instead of damaging his rule, because the average Russian may say ‘well, look, the West is turning their backs on us, so why should we like them? Why should we change anything?’ So, in the end, the action businesses have taken might actually worsen the situation. This is why we must be aware of that, but we are unable to evaluate that at the moment.

LJ: It seems to be a double-edged sword. On another note, you are very involved in the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFE), which ended a couple of weeks ago. Are you satisfied with this process? Was it more about the process than the outcome? How do you view this incredible initiative? Did it live up to your expectations?

AA: The jury is still out on CoFE. The Conference on the Future of Europe is formally over, but we do not know yet how will the European institutions and Member States react to these beautifully crafted 178 policy recommendations coming from the citizens who had been randomly selected from all across Europe.

I think the Conference went well, when measured against particular benchmarks. It did manage to create a transnational space, allowing citizens – who usually do not talk about Europe – to get involved, to feel that Europe is where they belong, and to formulate a set of expectations, which now have to be turned into reality by the EU.

We witnessed an incredible and unexpected flip of the traditional logic, according to which it is the institutions and the Member States who define what is next for the EU, whereas here it was the citizens who declared what they expect of the European Union. This premise will drive the next phase.

When we look at the quality of these recommendations, we may observe that they are not the typical proposals. Average citizens exhibited a desire to better understand what is happening at the different levels of governance in Europe – how decisions are made, what is at stake, how they can have a say in it and be heard.

In a nutshell, European citizens asked for a greater transfer of competencies from the nation state to the European Union – but not necessarily in a federalist way. They have asked for a set of reforms that would basically allow many more citizens (not only these 800 who were involved in the CoFE) to be a part of this process. There were ideas ranging from getting rid of the veto so as to make speedier decisions, to the idea of holding Europe-wide referenda, where citizens could decide the desired direction to take in a democratic manner.

There were policy proposals for the EU playing a greater role in public health, defense, taxation – the areas that would make the EU more sovereign and autonomous in its relations with other regions. This is a very powerful message, but the question is how with the EU institutions and Member States react now?

As of today, the European Council has to provide the first response to these recommendations. The Member States are split – twelve states, led by Sweden and major Visegrad countries, saying that they do not really want to reopen the treaties, and there is also a group of 4-5 major big countries (France, Germany, Italy, and Spain) saying ‘no, we are ready to start this process’, whereas the rest of the EU remains rather neutral and agnostic.

I do not sense much appetite for changing the treaties. I do not think it is going to happen in the coming days or weeks. The European Parliament is set to vote on this issue, but I do not expect it is going to be a traditional treaty revision. I would rather expect there to be some kind of arrangement on the intergovernmental level and some reforms (which are already being lined up – for example, in the area of public health or developing European transnational electoral lists, institutionalizing the Citizens’ Assembly).

Based on a study I conducted with my students a few weeks ago, it turned out that 90% of these recommendations do not necessarily require treaty changes. There is so much that can be done under the current treaties if there is a political will and agreement between the Member States and their leaders to actually start acting on these recommendations.

The podcast was recorded on June 8, 2022.

Find out more about the guest: albertoalemanno.com/

This podcast is produced by the European Liberal Forum in collaboration with Movimento Liberal Social and Fundacja Liberté!, with the financial support of the European Parliament. Neither the European Parliament nor the European Liberal Forum are responsible for the content or for any use that be made of it.

The podcast, as well as previous episodes, is available on SoundCloud, Apple Podcast, Stitcher, and Spotify.